Are you sure you want to leave 's MyShop site?

Are you sure you want to leave 's MyShop site?

Are you sure you want to leave 's MyShop site?

Are you sure you want to leave 's MyShop site?

Written by: Em Capito, LCSW, MBA, E-RYT, from the Health Sciences Advisory Board

Have you ever felt exhausted or not slept well? Have you ever struggled to wake up and get going even when you got a full night’s sleep? Have you had times where you felt less patient, less focused, or less creative?

If this has ever described you, you’re in good company, and many of us blame stress or “burnout” for our symptoms. However, stress isn’t always negative. Restoring energy, engagement, and overall wellness requires understanding how the mind and body functions optimally so we can build intelligent stress resilience.

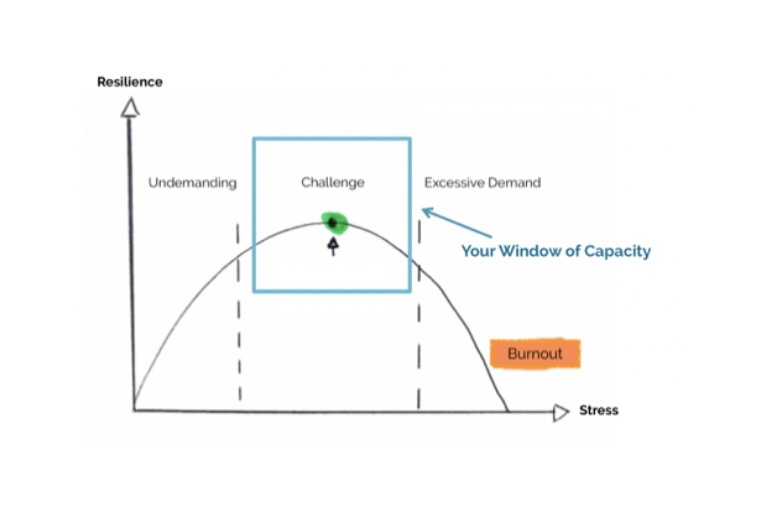

When we think about resilience, we often think of “bouncing back” from stress or challenges, but the aim of stress resilience isn’t to bounce. Resilience is a dynamic factor that fluctuates on a day-to-day or even minute-to-minute basis. By building stress resilience, we aim to widen our window of capacity so we can smooth out the impact of stressors and grow through challenges.

Stress is a transformative factor that can be a positive force for engagement and growth. Sometimes, though, we may experience too much or too little stress and find ourselves struggling to get back on track.

Resilience is like a muscle. When we exercise it regularly and intentionally, we build up resilience, which widens our window of capacity1 to encompass a greater range of life experiences. In other words, when we are resilient, we are more capable of feeling happy and fulfilled across a broad variety of challenges, from a sunny day at the beach with family to a high-pressure business presentation.

When we are outside our window of capacity with too few challenges in our lives, we experience underwhelm, which can lead us to withdraw further and feel like we are shutting down. When we experience too many challenges and feel overwhelmed, we tend to feel similarly, like we don’t have the energy or focus to engage fully in life.

Forgetting to exercise our resilience can be easy. Much like going to the gym, it can feel uncomfortable to stretch past our limits to grow. Especially when life is busy, we may avoid challenges that would normally interest us.

When we neglect our resilience for long periods of time, our window of capacity atrophies, or weakens, just like a muscle. Over time, our window of capacity can shrink and more and more can feel uncomfortable and overly difficult.

This is why many of us have struggled to get back to our prior levels of energy, sleep, and productivity after the isolation of the global pandemic. Most of us have been on a roller coaster of underwhelm as we withdrew from our normal life activities and then overwhelm as we tried to return to our lives while still experiencing continual threats outside our control.

When our resilience dips, we may experience greater anxiety, and we may start to live in a chronic sympathetic physiological state.

Broadly speaking, our nervous system fluctuates from a sympathetic state where the mind and body are reacting to challenging conditions to a parasympathetic state where the mind and body are calm and responsive.

Our baseline parasympathetic nervous system can be summarized as a “rest and digest” state. This is when the mind and body function optimally. We are at our best in this state.

When our brain senses a threat in the environment, it sends a combination of nerve and hormonal alarms. These alarms trigger the adrenal glands to release a surge of hormones that shift the nervous system into that sympathetic state, preparing us to survive. We categorize our typical survival responses as fight, flight, freeze, or fawn, which is why we often refer to this as a “fight or flight” state of being.

Keep this in mind: when there’s nothing to fight or run from, we tend to default to a “freeze” response, which can be unsettling for many of us who typically respond to stress by jumping in and working hard.

The stress hormones, which include adrenaline and cortisol, trigger a cascade of physiological changes2, which are quite helpful if we need to run away from a bear. These stress hormones elevate our heart rate, increase blood pressure, and release glucose (sugar) into the bloodstream to fuel our muscles. On a cognitive level, we are now thinking with the survival part of the brain rather than our prefrontal cortex, which is the part of our brain that can focus for long periods of time, store long-term memories, and think creatively. If we’re running from a bear, we simply need to run.

The threat response hormones become corrosive rather than helpful when they are deployed continually over time due to a constant state of stress outside our capacity to cope.

Living in a state of chronic stress can lead to anxiety, fatigue, sleep and appetite disruption, and can trigger autoimmune responses in the body that lead to chronic disease3. More immediately, remaining in a highly elevated state of stress can result in hypertension, heart attack, or stroke.

When we are outside our window of capacity for an extended period and our resilience has been reduced, it can be tricky to pull ourselves out of a toxic stress cycle.

Feeling “stressed” leads to fatigue and low productivity during the day, so we may counter with caffeine or naps and extended work hours, which can then undermine our sleep, which may already be of poor quality due to the anxiety triggered by stress hormones.

Interrupting this cycle can take a concerted effort. It can be helpful to assess our protective factors, which widen our window of capacity, and our risk factors, which can lead to burnout.

If we think about stress resilience on a hierarchy, the foundation consists of our basic needs, including sleep, fuel, exercise, and meaning 2,4.

Feeling bad doesn’t change our lives; passionately engaging in our projects and relationships is what drives us to take care of our minds and bodies.

One of our primary sources of meaning is found in our relationships 3,5. Plus, when we physically share space with other people who are in a calm, parasympathetic state, our nervous systems respond by mirroring that state and calming to match.

Overall, we cultivate meaningful lives by engaging creatively, deeply experiencing a moment or person, and consciously choosing an empowering attitude in the face of difficulty5. The prerequisite for meaningful experiences being present in the moment, which is why mindfulness tools like breathwork, meditation, and music can result in a more resilient, optimistic mindset.

Whenever we pause to observe the moment, we are open to curiosity, the anecdote to the threat response, which is perhaps the most helpful place to start: with this moment, right now.

Sources:

1 The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience

2 Resilience as a dynamic concept

3 Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators

4 Resilience and mental health

5 Frankl, Viktor E. (1962). Man's search for meaning: an introduction to logotherapy.

You are trying to view a MyShop page. Please log out in order to view this website.